Wednesday January 1st, 2018

The idea of capital appears to have many definitions, and the definitions depend on the application of the idea. From a review by Nan Lin (Connections, 22, 1999, 28-51) capital is an investment, but it is also a product. The idea of capital can be applied to finances or economies, individual humans, cultural values, or social entities (networks!). Reading about social capital reminds me of the parable of the blind men and the elephant. The definition that sticks with me comes from Lin: Individuals engage in interactions and networking in order to produce profits...Social capital is the investment in social relations.

Ok, so how does this relate to a chemistry classroom? Many - most - chemistry classes at colleges and universities are large classes. At VCU, general chemistry classes range in size from 200 to 400 students. Even upper level chemistry classes at VCU are large with 60-130 students. Typically, a chemistry classroom looks like this:

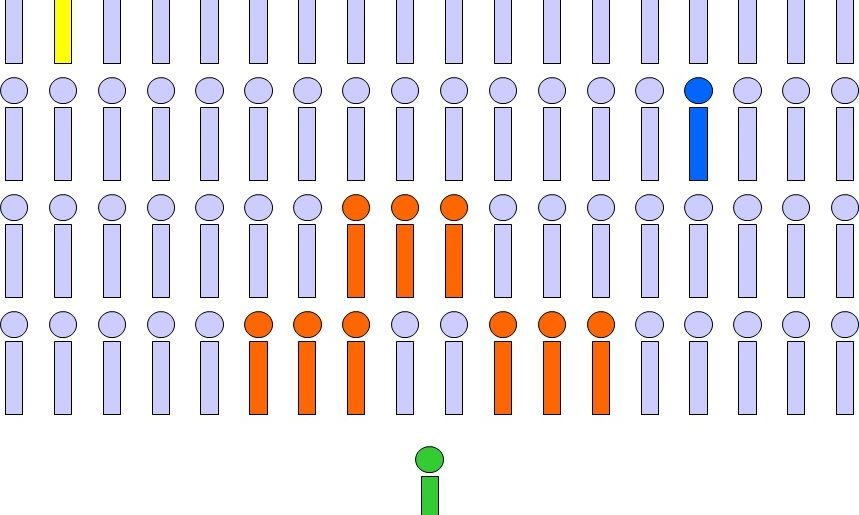

That could be me in the front, with the students all facing me. (It's also likely to be early in the semester because no one is absent.) If I teach using a traditional lecture format, I may get to know a few students sitting in the front and one or two students sitting in the back who do something to get noticed - ask many questions or come in late. The students sitting in the front may talk to one another, and it is possible that the student who I notice will also get noticed by other students. That classroom looks a bit like this:

Thinking network we might expect that the instructor (me, green) is linked to the orange students and to the blue and yellow students. Let's also suppose that the orange students talk to each other - maybe they sat together because they knew each other before the semester. In this network, the instructor (green) will have the highest measures of centrality. The network has very low density. The majority of the students are not linked to anyone. In fact, it would be a stretch to call this classroom a network.

By Lin's definitions, there is no "activation" of social capital in this classroom environment. Individuals work as individuals; there is no sharing, no collective profit, no investment in social relations (because there are no social relations!).

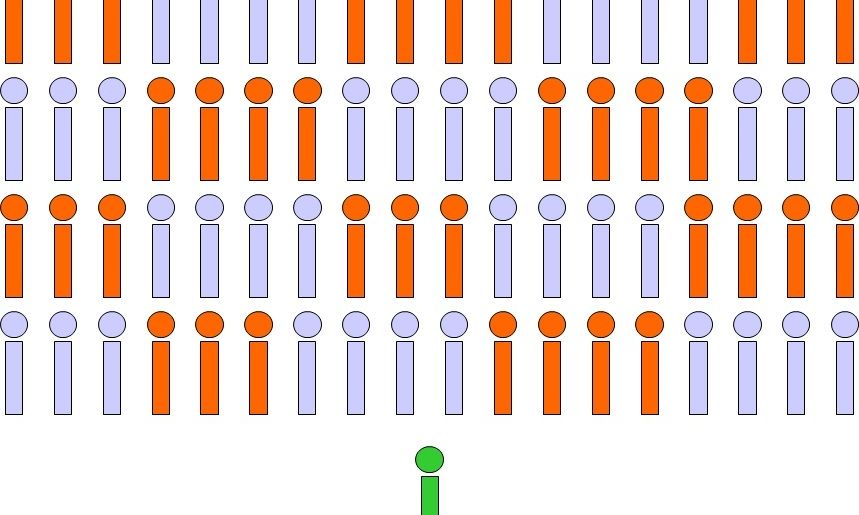

About 12 years ago, I adopted POGIL (Process Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning). Students in my classes work in assigned teams of four on guided inquiry activities that focus on the main course concepts. The activities begin with a model, and then students answer questions that first have them explore the model, then build concepts, and finally apply the concepts. Any lecturing that I do follows the activity. Here is what my classes look like:

Students are sitting with their teammates (teams of 3 or 4). They must work together to complete the activity, and each person on a team is assigned a role (such as timekeeper or spokesperson). They are interacting with each other throughout the class period. Frequently - because they are already talking - teams will interact with other teams seated nearby. In addition, I move throughout the room, answering questions posed by all the teams.

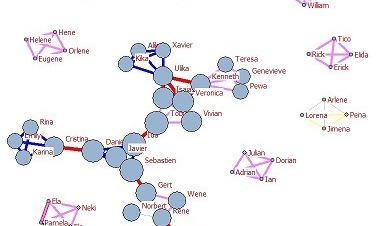

Now let's consider the resulting network. I now know every student in the class, and I am linked to each of them. The students know the other students in their team, and they know students in the teams around them. This network has a much higher density (than the network in the traditional classroom shown above). The figure below is diagrams the links that form in my POGIL classroom. The circles represent students (with fake names), with the size of the circle representing how close that student is to other students. The lines represent connections between students, with the line thickness representing the strength of the connection.

The social capital here is based on profit related to learning - and to getting better grades. The structure of the class is purposefully designed to encourage students to activate their ties and get the help they need. In this classroom environment, students are very likely to make judgments about their peers' reliability and ability, and they then use that to either help other students or to seek help from other students (analogous to the job seekers in the article by Sandra Susan Smith, "Don't put my name on it": Social Capital Activation and Job-Seeking Assistance among the Black Urban Poor, Amer. J. Soc., 111, 2005, 1-57).

The interplay of networks, social capital, and classroom structure lead to interesting questions that help us understand how students learn. Do students look to their peers for help? Which students willingly help other students? If they do, why - is it related to reputation or status? The same question can be asked if students don't ask for or give help. Do students identify certain other students - in their teams or in the whole class - as "smart", and how do they make this identification? Does assigning students to teams build a "better" network (activate more capital) than letting students choose their own teams? Finally, what about students who feel very different from their peers? Does requiring them to interact actually block learning for these students?

I don't have hard evidence (yet!) to answer these questions, but anecdotally I have found that most students do learn better and learn more deeply when I teach using POGIL than when I taught using traditional lecture. What is your experience?